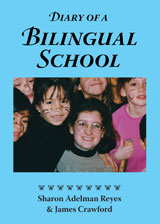

This article is an excerpt from the book Diary of a Bilingual School: How a Constructivist Curriculum, a Multicultural Perspective, and a Commitment to Dual Immersion Education Combined to Foster Fluent Bilingualism in Spanish- and English-Speaking Children

Fluent bilingualism is commonplace throughout much of the world. How strange that it’s so difficult to achieve in the United States! Unless we came here as immigrants, grew up in homes where another language was spoken, or spent extended time in a non-English-speaking country, most Americans are likely to be monolingual. Not a devastating handicap—English is dominant internationally and becoming more so—but hardly an optimal condition, either. Despite the controversy it sometimes arouses, bilingualism has indisputable advantages: social, cultural, academic, professional, even cognitive. The evidence is clear: Speaking two or more languages not only enriches our lives; it can also make us smarter and more successful. Recognizing these realities, increasing numbers of Americans are seeking effective language-learning opportunities for themselves and especially for their children.

American public schools are finally beginning to respond. Over the past twenty years, language immersion programs have mushroomed, both “one-way,” involving students from a single language background, and “two-way,” involving speakers of both target languages. While immersion models vary considerably in details, they have generally proven far more successful than the foreign-language classrooms that most of today’s parents were forced to endure. Rather than teaching skills out of context—remember the flash-cards, grammar exercises, artificial dialogues, and other mind-numbing activities?—well-designed immersion programs help students acquire a second language by using it for meaningful purposes, including subject-matter instruction. Such classrooms turn out graduates who tend to be much better at actual communication in the target language—more likely, for example, to converse easily with native speakers in real-life situations. These advances were made possible, in large part, by pedagogical insights gained from bilingual education programs for language-minority students in the United States and for language-majority students in Canada.

There’s another factor that also deserves mention: advocacy by determined parents, working in concert with educators who were able to contribute professional expertise and a willingness to take risks. Without such alliances, it’s unlikely that experiments in dual immersion would have ever been tried.

The founders of Chicago’s Inter-American Magnet School, Janet Nolan and Adela Coronado-Greeley, were both parents and educators. As parents, they organized community members to put pressure on the Chicago Public Schools and the Illinois State Board of Education. As professionals, they were able to access the growing research base on bilingualism to help with program design.

Janet had spent time teaching English as a second language (ESL) in Mexico, where she was impressed by young children’s capacity for language learning. Fluent in Spanish, though a nonnative speaker herself, Janet created a bilingual environment at home for her two preschool-age daughters. The initial results were promising. Yet it soon became clear that, to continue nurturing their Spanish development, more institutional support would be needed to balance the predominance of English outside the home.

Adela, a Mexican-American from East Los Angeles, was a community organizer who also worked at a school on Chicago’s South Side. Though she had grown up speaking Spanish, she recognized that her own children faced similar obstacles as Janet’s in becoming truly bilingual. So the two parent-educators joined forces to create what would become Inter-American.

Over a several-year period, they led campaigns to secure grant funding, find a building, hire teachers and aides, purchase books and materials, arrange transportation, and ultimately create a permanent dual immersion program. Their advocacy paid off when the Chicago Public Schools approved a bilingual preschool in the fall of 1975. Official designation as a magnet school, serving children from all language groups, finally came in 1978. The name Inter-American, suggested by the parent of a Spanish-dominant student, was quickly adopted.

Meanwhile, Adela and Janet drew on the pedagogical breakthroughs achieved in French immersion programs introduced in Quebec in the mid-1960s. Anglophone students there started school, learned to read, and were taught academic subjects in French, with lessons carefully adjusted to their level of proficiency. A class in English language arts was introduced in second grade, but most instruction continued in French. By the end of sixth grade, students achieved functional competence in the second language, at no cost to their academic progress when measured in English—a remarkable accomplishment. It turned out that, under the right conditions, bilingualism could be acquired incidentally and naturally. Over the years, variations of French immersion have become so popular that they now enroll approximately 317,000 Anglophone students throughout Canada.

Yet the one-way immersion model also has its limitations. Because English-speaking students rarely interact with native speakers of French, they often have difficulty developing native-like proficiency in French or close relationships with Francophone peers. At Inter-American, by contrast, the founders brought together children from Spanish- and English-language backgrounds, creating an educational environment that was both bilingual and bicultural. By learning together in the same classrooms, students from each group acquired a second language more effectively and also forged cross-cultural friendships and understanding. From the school’s beginnings, it embraced diversity, socioeconomic as well as racial and ethnic, while stressing respect for the two languages and the two language communities. Not surprisingly, Inter-American also encouraged the active involvement of parents, who were welcomed as an integral part of the school community and who participated in most important decisions affecting children. By the 1990s, it enrolled more than six hundred students from prekindergarten through eighth grade.

Initially, instruction was provided half in English and half in Spanish, a policy that required all teachers to be fully bilingual. This “50-50” model is common in dual immersion programs, often in response to parents’ anxieties. If my child is taught mostly in another language, they wonder, how will she keep up academically in English? While the concern is understandable, research shows it is largely unfounded. In well taught bilingual and immersion programs, whether one-way or two-way, the skills and knowledge that students acquire in one language easily transfer to another. Reading ability, for example, is something that children need to learn only once; it can then be applied to each new language they acquire.

By 1990, it became clear that Inter-American students were doing quite well in English, but their Spanish proficiency was lagging. The founders recognized that the minority language, which had limited support outside of school, especially for English-dominant students, needed a stronger emphasis in the classroom. So they adopted an “80-20” ratio of Spanish to English from prekindergarten through fourth grade, combined with ESL and SSL (Spanish as a second language) as needed. Until the end of second grade, children were taught reading primarily in their native language. This was the dual immersion model during the 1995–96 school year in which our story takes place, and it proved quite successful. Academic outcomes at Inter-American have been impressive, with students from both language groups scoring well above city and state norms in English and Spanish.

What has further distinguished dual immersion schools like Inter-American, contributing to their successes, is a break with traditional, teacher-centered classrooms in favor of constructivist approaches that guide rather than prescribe what children learn. In many ways, this change has been less a conscious choice than a practical necessity.

As the Brazilian educator Paulo Freire once said, “Reading the world always precedes reading the word, and reading the word implies continually reading the world.” The same principle applies to the process of becoming bilingual.

It is only natural, then, that dual immersion tends to incorporate constructivist strategies. Indeed, the fact that it does so may help to account for its academic successes, especially for English language learners (a hypothesis that admittedly remains untested by researchers). This is not to say that most dual immersion programs are constructivist by design. Far from it. For teachers in these schools, the label is often unfamiliar or poorly understood. The primary focus tends to be on bilingualism, especially on how the two languages are used for instruction, rather than on questions of educational philosophy. Where dual immersion programs are academically impressive, as many are, the results have usually been attributed to linguistic rather than curricular factors. So their constructivist features tend to be overlooked.

In addition, today’s relentless pressures for “accountability” are pushing schools away from student-centered pedagogies and toward rote teaching of material likely to appear on achievement tests. Despite their popularity with parents at the local level, dual immersion programs are not exempt from state and federal mandates that place “high stakes” on test results. Low scores can close a school, derail an educator’s career, or keep a student from graduating. It’s no wonder that, in many classrooms, test-prep activities have become a substitute for actual teaching, especially for English language learners and other minority children. Even well-established dual immersion programs must now strike a balance between “covering the standards” and fostering language acquisition.

Despite these obstacles, however, constructivist approaches remain possible where committed educators find spaces in which the excitement of learning can break out. We believe that dual immersion is one of those spaces.

Stay tuned for Part II of this article featuring a view of classroom dynamics in a two-way immersion program.

This is an excerpt from the book Diary of a Bilingual School: How a Constructivist Curriculum, a Multicultural Perspective, and a Commitment to Dual Immersion Education Combined to Foster Fluent Bilingualism in Spanish- and English-Speaking Children, published by DiversityLearningK12 (www.diversitylearningk12.com), January 2012.

[…] THIS ARTICLE No comments In “Fostering Bilingual Education through Two-Way Immersion,” we describe how a constructivist curriculum and a multicultural approach to dual immersion led to […]